Suzuki Harunobu

c. 1725 - 1770

ca. 1770

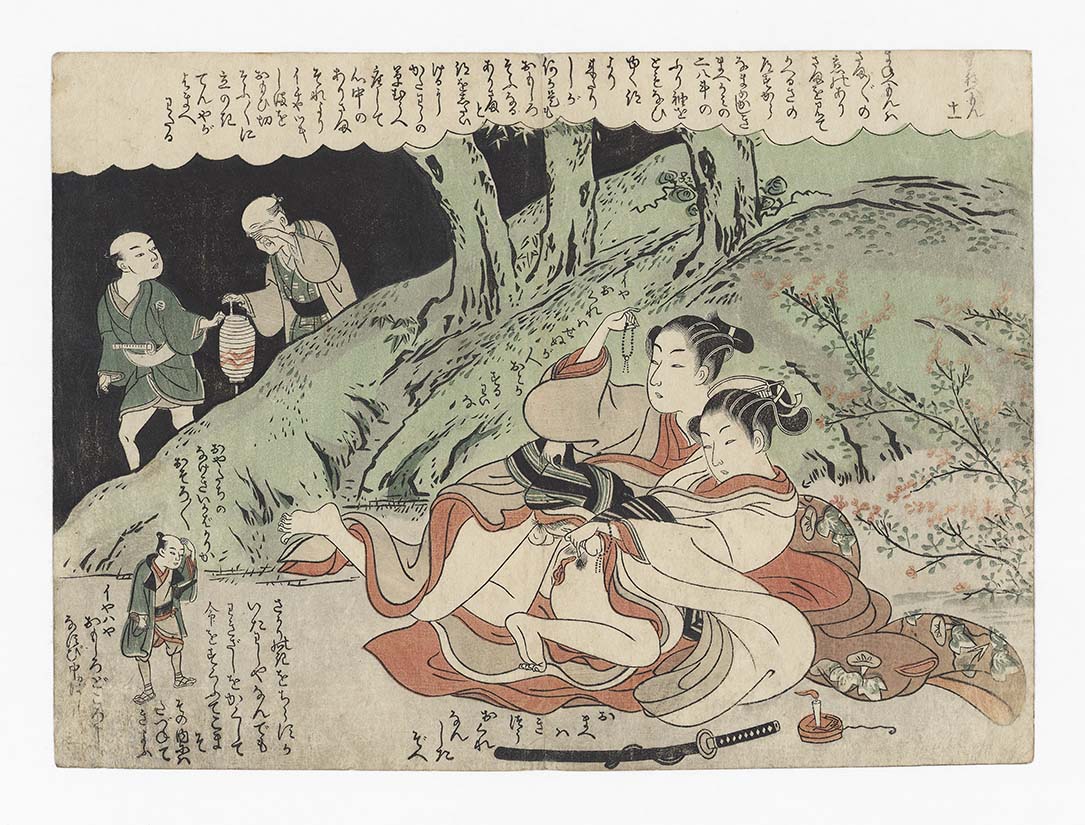

Horizontal chuban, 202 x 277 mm

Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi

Date: ca. 1770

Series: Elegant Amorous Mane'emon, eleventh plate

Furyu Enshoku Mane’emon

Fine impression and colour, some trimming at the top, vertical centerfold, otherwise very good condition.

The series Furyu Enshoku Mane’emon is one of Harunobu's acknowledged masterpieces. The set, created in the year of the artist’s death, introduced two important innovations in the shunga genre. The first and the most important is the creation of a pictorial story, which links all the plates in a sequence.

As a rule, in shunga sets, new characters and new settings were introduced with every picture and the pictures were not sequentially related. The second innovation concerns the number of prints: shunga were usually published in set of twelve. Mane’emon, however, is composed of two sets, consisting of twelve prints each.The name Mane'emon is a pun; it implies that its bearer is both an imitator (from the verb maneru, ‘to imitate’) and a tiny man of about the size of a bean (mame). The storyline of Mane'emon is that, once he has changed his shape, the hero starts on an erotic study tour that will take him to various places in eastern Japan. Harunobu uses this device to depict, in the first half of the series, the sexual life of the common people in Edo and its surrounding countryside and, in the second part, the customs of Yoshiwara, Edo's only licensed quarter. On each print of the set we find Mane'mon's observations and comments on the different aspects of Eros that he witnesses. The upper part of each print is taken up by an explanatory note or a haiku. There are, however, also short legends elsewhere on the print. These are comments and lines of dialogue, supposedly spoken by the characters themselves.This print shows Mane'emon as witness, in the middle of the night, of the love suicide of a very young couple, a common theme in kabuki theater and literature. The boy, who holds a Buddhist rosary in his right hand, seems disturbed by two figures on the left background: a desperate father who is looking for the young suicides. Near the couple there is a short sword. But the dialogues defuse the situation: the girl declares her determination to commit suicide but she actually alludes to her determination to perform the sexual act. Mane'emon states his intention to steal the sword to prevent suicide.

References:

Inge Klompmakers, Japanese erotic prints, shunga, by Harunobu & Koryūsai, Leiden and Boston, 2008.Gian Carlo Calza, Il canto del guanciale e altre storie di Utamaro, Hokusai, Kuniyoshi e altri artisti del mondo fluttuante, London and New York, 2010.David Waterhouse, The Harunobu Decade, a Catalogue of Woodcuts by Suzuki Harunobu and his followers in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Leiden, 2013.Aa Vv, Shunga: sex and pleasure in Japanese art, catalogue of the exhibition at the British Museum, London, 2013.

Price on application

Information on the master

There is no doubt that Harunobu ranks as one of the most enchanting masters of ukiyo-e in 18th century. He is said to have studied under Shigenaga, but his early prints are in the Torii and Toyonobu manner. By 1762, however, he had already developed his unique style, which was soon to dominate the ukiyoe-e world.

In 1765 there was a revolution in Japanese woodblock printmaking. Toward the end of 1764, Harunobu was commissioned to execute a number of designs for calendar prints for the coming year. Various noted literati of Edo contributed designs and ideas, and the printers outdid themselves to produce technically unusual work. From this combination of talents was born the nishiki-e (brocade picture) and the surimono genre was also beginning to emerge. These prints were issued at New Year, 1765. Harunobu’s full genius for both colour and line was quickly developed by this new technique. He was able to attain a polychrome brilliance in his prints whose standards have seldom been superseded. Though we know nothing of Harunobu's formal education, he was certainly one of the most literate of the ukiyoe-e artists. In many of his prints, verses and design are wedded in a happy combination seldom seen before or after, and his ideal of femininity was one of the most influential in the history of ukiyo-e.

Other works of the master